Like most others, Lenovo too had a small and humble start way back in 1984 when its founders established the firm in China. They did pretty good business in China but not much abroad until 2005 when they acquired IBM’s PC business. So how did they become numero uno?

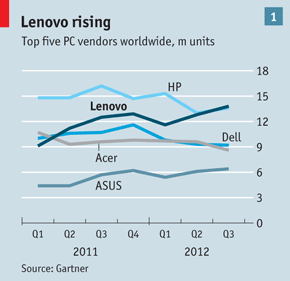

In the third quarter of last year, Gartner, a consultancy, declared Lenovo the world’s biggest seller of PCs, ahead of Hewlett-Packard (HP). It is number one in five of the seven biggest PC markets, including Japan and Germany. Its mobile division is poised to leapfrog Samsung to grab the top spot in China, the world’s biggest smartphone market.

So, what really happened here? How did this turnaround take place suddenly?

Lenovo’s recovery owes much to a risky strategy, dubbed “Protect and Attack”, embraced by the firm’s current boss. After taking over in 2009, Yang Yuanqing moved swiftly. Keen to trim the bloat he inherited from IBM, Mr Yang cut a tenth of the workforce. He then acted to protect its two huge profit centres—corporate PC sales and the China market—even as he attacked new markets with new products.

Unlike most who predicted that IBM will actually pull down Lenovo further, shipments have actually doubled since the deal, and operating margins are thought to be above 5%.

Unlike most who predicted that IBM will actually pull down Lenovo further, shipments have actually doubled since the deal, and operating margins are thought to be above 5%.

Amar Babu, who runs Lenovo’s Indian business, thinks the firm’s strategy in China offers lessons for other emerging markets. It has a vast distribution network, which aims to put a PC shop within 50km (30 miles) of nearly every consumer. It has cultivated close relationships with its distributors, who are granted exclusive territorial rights.

In 2011 Lenovo bought Medion, a European electronics firm, for $738m, which doubled its share of the German PC market. The same year it spent $450m to enter a joint venture with NEC that made it the largest PC firm in Japan. In 2012 it paid $148m to buy CCE, Brazil’s biggest computer firm. It is also opening factories in markets, including America, where it is surging.

Well, it’s not all good news always like they say. Although the “Protect” part works well, the “Attack” part is actually the tougher job. The attacking only causes the company to lose money. In most markets outside China, Lenovo’s mobile phones, tablets and consumer PCs (as opposed to corporate sales of ThinkPads) lose money.

“Profit is the long-term goal,” says Mr Yang, “but it helps to have a large revenue base.” He vows to keep investing, regardless of returns, until the firm reaches a roughly 10% share in each of the target markets. Only with such scale is long-term profitability possible, he insists. Wong Wai Ming, the firm’s chief financial officer, is confident Lenovo will eventually double its pretax profit margin of 2%.

With inputs from The Economist (Read More).